By Dan Mitchell

I have repeatedly warned that nations get in fiscal trouble when government is too big and growing too fast.

In such countries, it’s very common to find high levels of government debt as one of the symptoms of excessive spending.

This can create the conditions for a fiscal crisis, particularly during an economic downturn. Simply stated, investors (the people who buy government bonds) begin to worry that governments may renege on their promises (i.e., default).

There’s a must-read story on this issue in today’s Washington Post suggesting that the economic fallout from coronavirus has created conditions for new fiscal crises in nations across the globe.

Authored by Alexander Villegas, Anthony Faiola and Lesley Wroughton, the report explains that the downturn has produced record levels of debt.

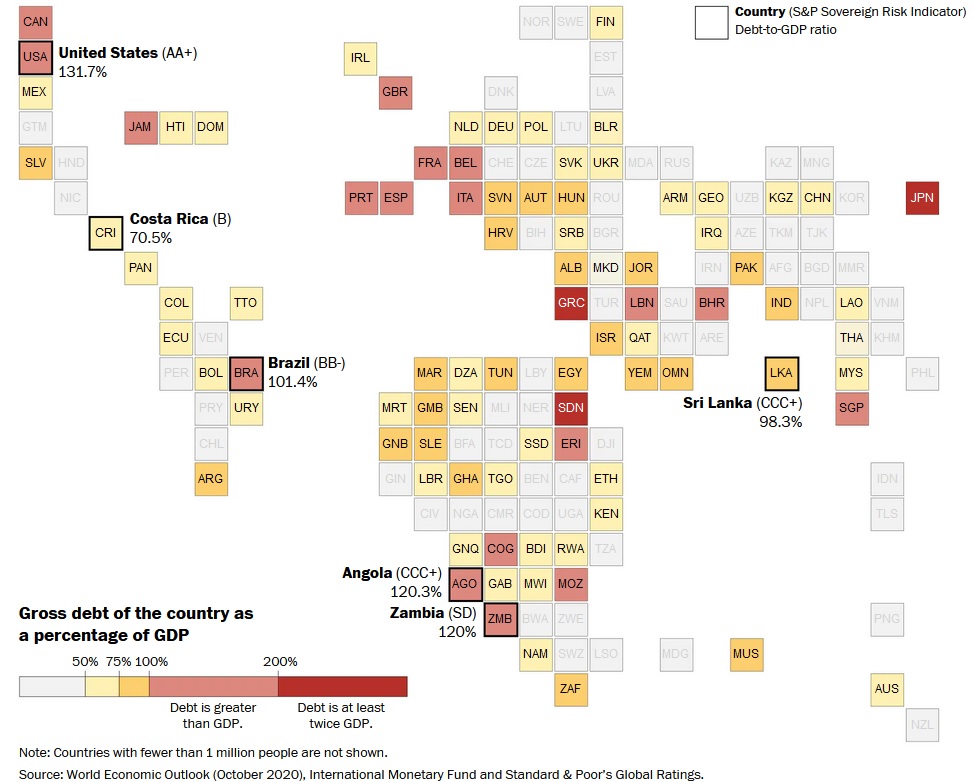

Around the globe, the pandemic is racking up a mind-blowing bill: trillions of dollars in lost tax revenue, ramped-up spending and new borrowing set to burden the next generation with record levels of debt. In the direst cases — low- and middle-income countries, mostly in Africa and Latin America, that are already saddled with backbreaking debt — covering the rising costs is transforming into a high-stakes test of national solvency. …By the end of 2020, total government debt worldwide was projected to soar by $9 trillion and top 103 percent of global GDP, according to the Institute of International Finance — a historic jump of more than 10 percentage points in just one year. Countries have maxed out their figurative credit cards.

Keep in mind, by the way, that spending burdens were climbing in most nations, leading to more red ink, even before the pandemic.

That was true in developed nations (the U.S., Europe, Japan), but also in developing nations.

And, the story explains that developed nations are far more vulnerable to fiscal crisis.

The pandemic is hurtling heavily leveraged nations into an economic danger zone, threatening to bankrupt the worst-affected. Costa Rica, a country known for zip-lining tourists and American retirees, is scrambling to stave off a full-blown debt crisis, imposing emergency cuts and proposing harsher measures that touched off rare violent protests last fall. …Angola, in contrast, effectively shut out of global markets, is racing to strike a deal with the Chinese, but even that might not be enough to prevent a painful debt crisis. Sri Lanka, locked in recession, needs to make $4 billion in debt payments this year with only $6 billion in the bank. Brazil’s debt, worsened by a yawning budget deficit, has surged to a crippling 95 percent of GDP — raising alarm over the medium-term ability of the Latin American giant to stay afloat. …Zambia, once a shining example of Africa’s economic renaissance, is now the Ghost of Crises Future for debt-burdened countries slammed by the pandemic. The sub-Saharan nation fell into default in November.

Here’s a visual from the report.

To simplify, it’s good to be in a lighter-colored nation and bad to be in a darker-colored country. At least in terms of national debt burdens.

All this grim data understandably raises the very important question of what choices governments should now make.

Sadly, some self-styled experts are actually urging even more spending, mostly because of a dogmatic belief in the supposed elixir of Keynesian economics. In other words, they want governments to dig a deeper hole.

Analysts argue that the need for stimulus to keep economies running during this historically challenging period still outweighs the need to balance budgets. …the IMF…is telling countries that now is not the time to scrimp, lest they jeopardize still-fragile economic recoveries.

Politicians will want to follow that advice because it tells them that their vice (buying votes with other people’s money) is a virtue (more spending magically can boost growth).

In the real world, there are two big lessons we should learn.

- First, it’s profoundly reckless to further increase tax and spending burdens when nations are already in trouble because of previous bouts of fiscal profligacy.

- Second, countries should focus on spending restraint in both the short run and long run, ideally by enacting caps to limit annual spending increases.

For what it’s worth, the U.S. would be in great shape today if, back in 2000, lawmakers had adopted a Swiss-style spending cap.

P.S. One reason that spending caps work so well is that there’s built-in flexibility when dealing with economic volatility.

P.P.S. Financing government with the printing press won’t work any better than financing it with taxes and debt.

Daniel J. Mitchell is a public policy economist in Washington. He’s been a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute, a Senior Fellow at the Heritage Foundation, an economist for Senator Bob Packwood and the Senate Finance Committee, and a Director of Tax and Budget Policy at Citizens for a Sound Economy. His articles can be found in such publications as the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Investor’s Business Daily, and Washington Times. Mitchell holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in economics from the University of Georgia and a Ph.D. in economics from George Mason University. Original article can be viewed here.

Self-Reliance Central publishes a variety of perspectives. Nothing written here is to be construed as representing the views of SRC.